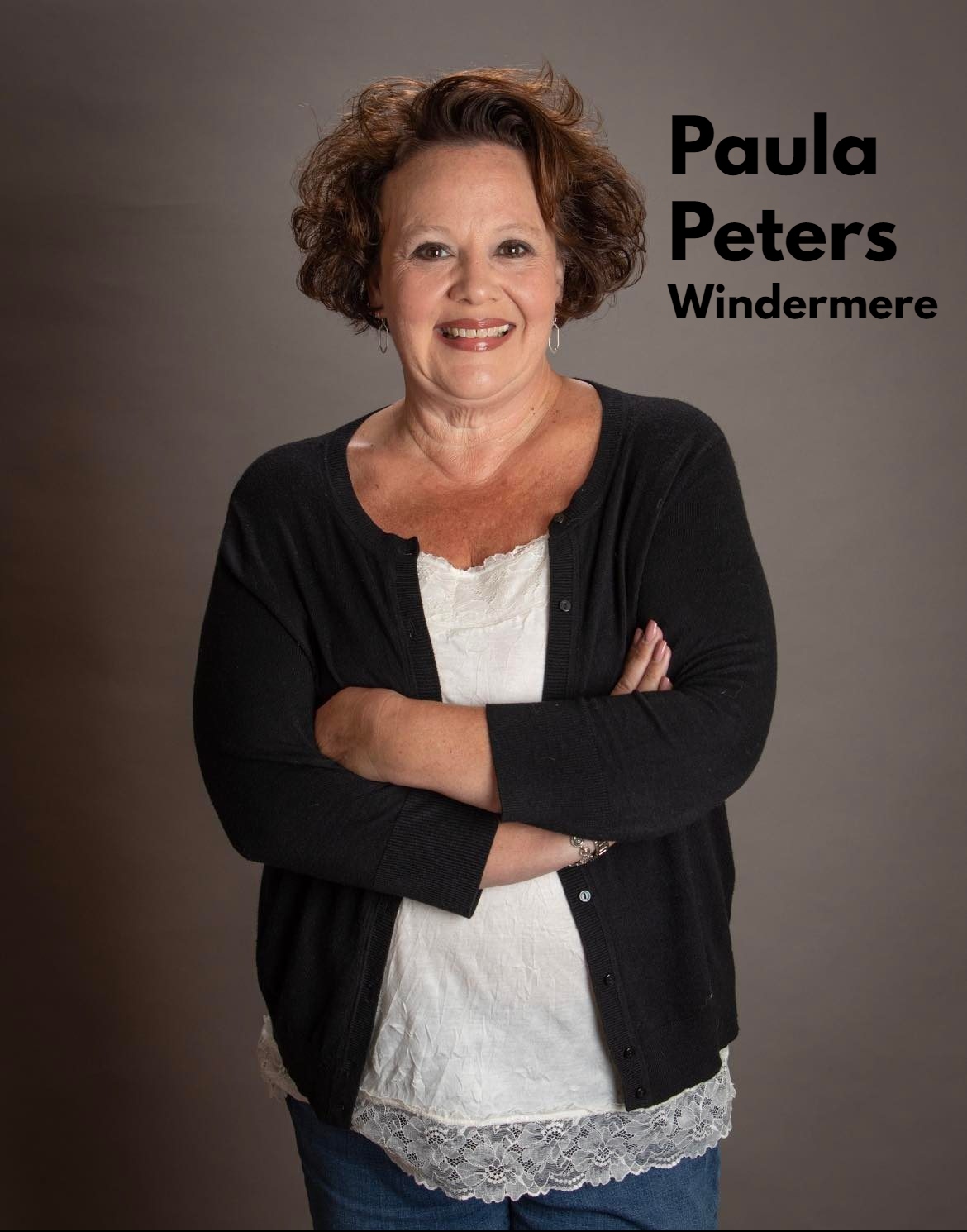

Former Wolf star Ben Biskovich and wife Karin compete in a race around Lake Massabesic in New Hampshire.

“I was never the most gifted athlete on the field, but I always felt like I was the smartest and best prepared. No one was going to out work or out hustle me.”

By the time he graduated in 1991, Ben Biskovich had left an indelible mark on Coupeville High School.

A three-sport athlete (co-captain in football and basketball and a state finalist in the 110 high hurdles in track), he might not have been the star (“I was never the MVP, I always got Most Inspirational or the Coach’s Award”), but he was the kind of rock-solid, never-back-down competitor who opponents remember years later.

His example is one that should resonate with every current Wolf.

“Have a great time, it goes fast,” Biskovich said. “Train, practice and play like you’ve got something to prove, like you’re fighting for a roster spot and don’t want to be taken off the field or court, so that afterwards you have no regrets.

“Win or lose you can look at yourself in the mirror and say, “I could not have done anything more”,” he added. “Then take that same attitude and effort into the class room and then the work force.”

Driven by that attitude, Biskovich was a constant surprise, often soaring to heights even he didn’t quite expect.

During his junior year of basketball he was aiming to be the sixth man for the Wolves, only to be tabbed as the team’s starting center over a senior who had a solid four inches on him.

At six-foot-one (“on a good day”), Biskovich was suddenly manning the middle for CHS.

“Everyone was surprised. Was there a shorter team in school history?,” Biskovich said with a chuckle. “I wasn’t a great shooter, they didn’t run any plays to get me open, but I did my job.

“I blocked out, I was tenacious trying to deny my much taller counterpart the ball, I trailed fast breaks at full speed just in case, and I fouled out quite a bit,” he added. “I worked my tail off for that starting spot and continued to do so because I didn’t want to lose it.”

Win or lose, one thing was for certain — Biskovich was going to be up in your grill all night long. Even when the Wolves faced off with Bush, whose SHORTEST player stood six-foot-five.

“If we were losing a basketball game, I would basically do a one-man full-court press and be completely worn out by the end,” he said. “You know, trying to leave it all out on the court, so after the game I could hold my head high and say, I gave it everything, there was nothing else I could have done. They were just better than us tonight.”

His work ethic and competitiveness probably reached its zenith during football, however, when Biskovich led the team in receptions and interceptions his senior season.

That 1990 squad was a perfect 9-0 in the regular season, including a landmark butt-whuppin’ of arch-rival Concrete, and went into the playoffs ranked fifth in the state.

While things ended prematurely, with a windblown home loss in their playoff opener, that Coupeville gridiron team ranks as perhaps the best in school history.

Running “speed demon tailback” Todd Brown behind bruising linemen that included Frank Marti, Brad Haslam, Matt Cross, Todd Smith, Nate Steele, Mark Lester and Chris Frey, the Wolves were hard to stop.

If a team stepped up, quarterback Jason McFadyen was an expert at using a play action pass, often with Biskovich as the target, to tear off huge chunks of yardage.

While the wins were huge, two other things remain as big or bigger in Biskovich’s memory.

The chance to play in front of his family, including his father, who had a long commute, and his mother, who still sports a “#1 Wolf Fan” license plate on her car, was huge.

“My dad drove up from Medford, Oregon to watch every single football game my senior year. Each way traveling nine hours to Coupeville, even farther to Darrington, Concrete and Friday Harbor,” Biskovich said. “When I look back at that season, that’s what stands out most.”

Football also brought him face-to-face with Ron Bagby, the coach who had the deepest impact on him as a young athlete.

“I loved Coach Bagby. I never remember him yelling at us, maybe raising his voice to get our attention, but never grabbing our face-masks and belittling us,” Biskovich said. “I wanted to practice hard and play well because I didn’t want to disappoint him.”

During his sophomore season, Biskovich was brought up from JV after the team’s starting tight end got in trouble. Stepping on the field for the last home game of the 1988 season remains one of his greatest sports memories.

“I had just turned 15. I hadn’t thought about that in a long time, but as I recall, it’s pretty awesome to get called out in front of your home crowd on a Friday night under the lights for the first time,” he said. “I was so nervous, I just didn’t want to false start.”

During the week of practice leading up to that game, Biskovich ran a route the way he thought Bagby wanted it run, only to have the coach not agree. It became a learning moment for him, one which helped drive him over the next two seasons.

“He called me over, put his arm around me and said, “Biskovich, I thought you were the one kid on this team I would never have to repeat myself to.” Wind out of my sails; I had disappointed him. I would like to think I never did again.”

The lessons he learned during his time at CHS have carried over into real life for Biskovich.

“I use the teamwork analogy all the time at work and in my marriage,” he said. “Everybody has to do their job and trust that everyone else is as well.

“Work ethic — working all summer lifting weights, running and practicing until you throw up, to achieve a goal six months down the road,” Biskovich added. “After being at my current job for a couple of years, I was talking with my boss at a Christmas party and it came up that I played high school football.

“He smiled and said, I should have known as much. Football players know what hard work and teamwork are all about.”

After high school, Biskovich went on to graduate from the University of Washington with a BS in Psychology. He later added a Master’s degree in physical therapy, meeting wife Karin, a high-level triathlete, in grad school.

They now live in New Hampshire with two young daughters and are partners in three physical therapy clinics.

His wife, who finished second in her age group at both the 2014 USAT National Championships and ITU World Championships, spurred Biskovich back into competitive sports.

While he had been a successful short distance man in high school, he had refused to run distance races as an adult (“It’s boring and bad for your knees”), but finally caved and ran a 4th of July 5K.

And he was back.

“I finished OK, I think around 23 or 24 minutes and I was like, “I can do better than that!” I was hooked. I had forgotten how much I missed competition.”

Now Biskovich runs about a dozen road races a year, from 5Ks with daughters Violet and Brynn, to marathons, including the 2013 New York City Marathon.

“I ran a 3:30 this last year in Hartford, which leaves me five minutes from my long term goal of qualifying for Boston … if I was 4 years older,” Biskovich said. “That’s what I love about running. It gives me a something outside of work and kids that I can actually control, short and long term goals.”

With both parents being passionate athletes, the Biskovich children have already picked up a healthy lifestyle. The hardest working man in Wolf Nation is delighted to see his progeny following in his footsteps.

“Work ethic, team work, healthy lifestyle, fun and friends in no particular order,” he said. “They’ve both tried a ton of different sports, you name them, gymnastics, soccer, swim team, 5Ks, triathlons, softball, skiing and most recently basketball and flag football.

“Violet is the only girl on the football team and she loves it!”

And why not? It’s a family tradition.